The River Kent flows through the heart of the town of Kendal and has the highest level of protection afforded to a river in Britain, being both a Site of Special Scientific Interest and a Special Area of Conservation. It is also just outside of the Lake District National Park, and is often billed as the “Gateway to the Southern Lakes”. A number of features that the river Kent has been designated for are likely to be impacted by Kendal Flood Risk Management Scheme.

14th April 2021 — Comments are off for this post.

Kendal Flood Risk Management Scheme – Overview

22nd June 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

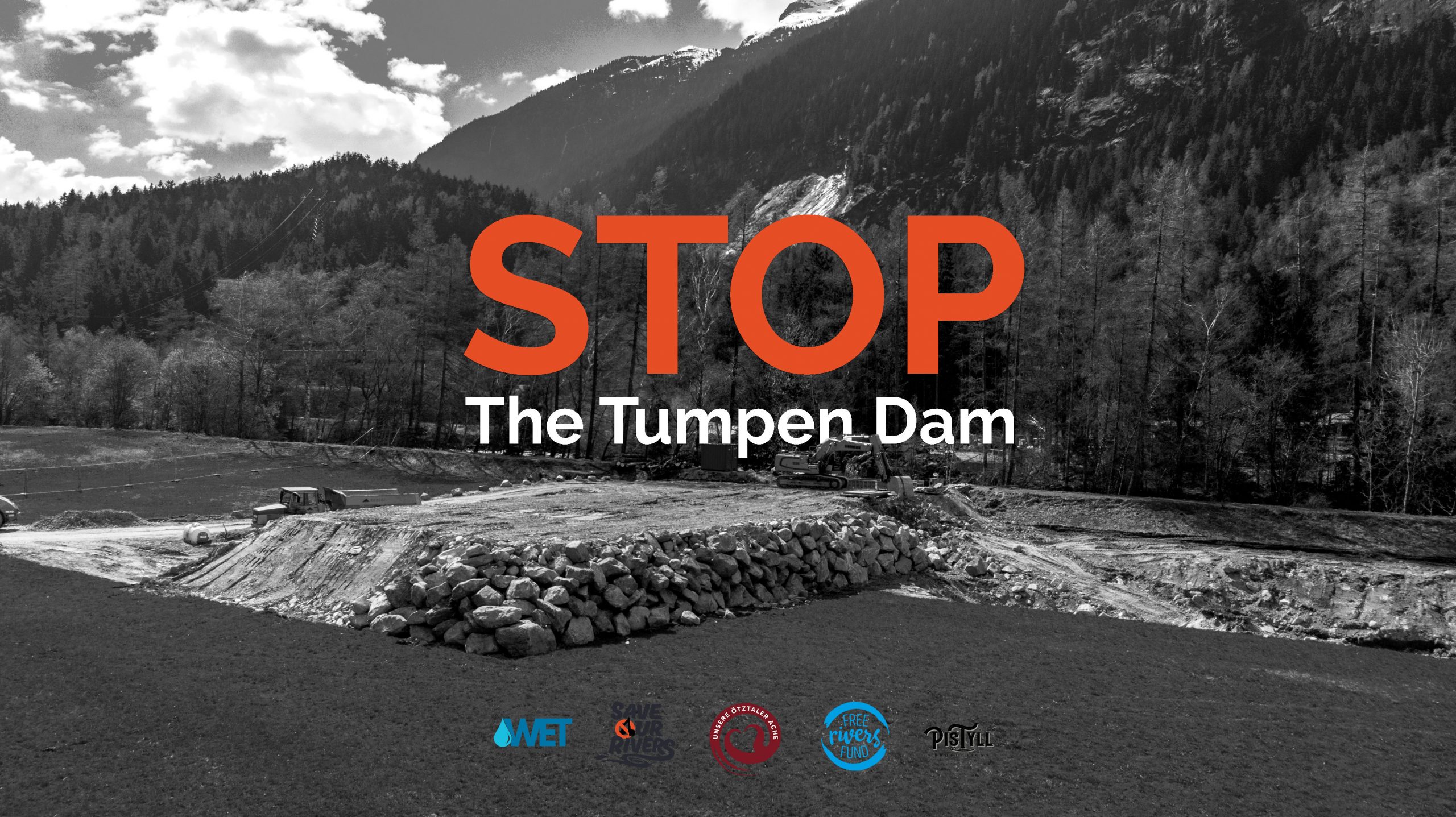

Scientists, Conservation Bodies and Luders stand up for Austrian Rivers

Since the handover of the petition against the building of the Tumpen Dam on 3rd June things have moved forward on the campaign to preserve Tyrol largest remaining free-flowing river.

Legally the case against the Tumpen Dam has still not be resolved, the outstanding legal complaint by WWF Austria has recently been thrown out by the court. However, a complaint by the local community is still outstanding and is currently being handled by a court in Vienna. There is also recent evidence that the construction did not gain approval by the local community when the original construction permit was granted 10 years ago. Ötztal power plant lacks a municipal council decision.

The insulting of the WWF Austria representative, with Minister Josef Geisler referring to her as a "Widerwärtiges Luder / Disgusting Bitch" has led to widespread condemnation amongst the German-speaking press and the centre right party's coalition partners in government, the Greens (despite one of them being present at the time and saying nothing). Somewhat of a cultural phenomenon followed with Austrian satirists getting involved, drinks being named "Luders" in popular bars and even a fashion brand printing a T-shirt.

The real issue however was the revealing of the level of respect that the Tyrolean Government holds for environmental experts. And the continuing issue with hydropower projects in protected areas being pushed through against European Environmental Laws on the basis of "public benefit". A "public benefit" that has been ascertained through a purely political agreement with no consideration of ecological of social impacts.

The Tumpen Dam is far from the only hydro project to have construction started before all legal concerns are dealt with and in clear contravention of European Water Framework Directive. A huge new reservoir is being built on the Längentalbach resulting in the destruction of the stunning Längenental valley and the capturing over 80% of the catchments glacial run off.

As a response WWF Austria have presented the government with a list of a 8 demands to launch a fresh start for Tyrolean nature conservation.

WWF Austrias demands here in German and below translated to English.

1. Create structural clarity: The distribution of responsibilities in nature conservation and water management needs to be clarified: Nature conservation and water protection needs to be managed by a single department

2. Strengthen water protection: Permanent protection granted for all currently protected waterways and the free-flowing stretch of the Inn from Imst to Kirchbichl (without expiry date) in the Tyrolean Nature Conservation Act.

3. Stop excessive hydropower expansion plans: Many plants are still being planned in the ecologically best stretches of water. Although the state has drawn up a catalogue of criteria for hydropower, damage to nature continues without restrictions. Hydropower plants that are not recommended must lead to rejection in the future.

4. End political directives to the detriment of nature: Political influence on nature conservation to the detriment of nature must come to an end. Inglorious examples of this are the Lesachbach power plant and the Tumpen power plant.

5. Ensure public participation and fair procedures in accordance with the Aarhus Convention: No construction of controversial projects until all open legal questions have been clarified.

6. Design flood protection by working with nature: The commitment to ecological flood protection must be taken seriously. Our rivers need more space. Following the example of Lech, correspondingly large projects on the Inn and other watercourses should also be implemented.

7. Create glacier protection without exceptions: The country must commit itself to the unconditional protection of glaciers and protect the "soul of the Alps".

8. Restore the nature conservation fund: The curtailment of the funds of the only financing instrument for nature conservation must be corrected.

WWF Austria

More than 60 Austrian scientists have also expressed their concerns about the advancement of hydropower in Austria in an open letter to the federal government. The signatories of the open letter, all experts in water ecology and biodiversity at several institutes in Austria, make it clear that an extension of hydroelectric power, which is not coordinated with the ecological goals, in particular the construction of new small hydroelectric power plants, is incompatible with sustainable development. The scientists agree that small hydroelectric power plants contribute little to energy supply due to their low performance and cause the disproportionately high environmental damage.

There letter can be found here in German or translated below:

Innsbruck, Graz, Salzburg, Vienna on 10.6.2020

Dear Federal Minister Gewessler, BA, dear Mr. Vice Chancellor Mag. Kogler.

It is with great concern that we observe the advancement of hydropower as part of the expansion of renewable energies, especially in connection with the Renewable Energies Expansion Act (EAG).

As scientists from the fields of water ecology and biodiversity we are very alarmed. The recently published biodiversity strategy of the European Commission asks for a more sustainable use of renewable energy sources, which serves both to decarbonise the energy system and to counter the loss of biodiversity. It also asks for 25,000 kilometres of waterways to be converted back into free-flowing rivers - a clear commitment to renaturalization being the task of the 21st century. We have been trying for years to comply with the Water Framework Directive and to improve the ecological state of our waterways, which already suffer a variety of impairments.

The expansion of hydropower that is not coordinated with ecological objectives, in particular the construction of new small hydropower plants, contradicts the principle of sustainable development. This further aggravates the biodiversity crisis of our waterways. Their ecological status will deteriorate further rather than improve. We feel obliged to oppose this (as a) threat to our future.

In the past, thanks to green energy subsidies, new hydropower plants have been built also in protected areas and ecologically valuable waterways. Due to their little output, small hydropower plants contribute only an insignificant amount to the power supply, but cause disproportionately high ecological damage. The high degree of development of hydropower in Austria is already causing fragmentation of watercourses with over 5,200 constructions. The cumulative effect of multiple projects - that individually examined all appear environmentally sound - is strongly underestimated. In sum they impair water networks as habitat-connecting corridors and thus strongly affect the preservation of biodiversity. With increasing fragmentation and degradation of valuable habitat it will be impossible to halt, let alone reverse, the current trend of biodiversity loss.

Righteously, the current government programme states that the expansion of green energy is to be carried out under "observance of strict criteria with regard to ecology and nature conservation". We see a high risk potential in particular in the promotion of small scale hydropower and appeal to you urgently, to rethink their role within the framework. From the Green Party in particular we expect the integration of scientific expertise - as it is the case in climate sciences - into the design of frameworks that are relevant to water ecology. To only involve the energy industry, the social partners and the association of industrialists into the lawmaking process as of now is just not enough.

In conclusion, we would like to emphasise that we recognize and support the great importance of the decarbonization of Austria's energy supply. But the far-reaching transformation of the energy system must not aggravate the biodiversity crisis.

We urge you to contact the scientific experts. We want to contribute our expertise constructively, and we are also happy to work together with specialised nature conservation organisations.

5th June 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

22,800 Object to the Tumpen Dam

Wednesday, 3rd June representatives from Save Our Rivers,WET – Wildwasser erhalten Tirol, WWF – Austria and the Citizens' Initiative Against Tumpen Hydropower Plant presented a petition calling for a halt to the construction of a hydroscheme in Tyrol's largest free-flowing river.

The petition was received by LH-Stvin Ingrid Felipe and LH-Stv Joseph Geisler at Landhausplatz in Innsbruck.

As the WWF representative was discussing the impact that the continued construction of hydro schemes was having on Austrian river systems with LH-Stv Joseph Geisler he tried to interrupt her statement and when she continued Geisler turned to LH-Stvin Ingrid Felipe and described the WWF worker as a "Widerwärtiges Luder" (translation: "Disgusting Bitch").

The exchange highlights not only the stubbornness with which the Tyrolean Government pursues its' outdated energy policy, against both the advice of its' own environmental experts and European Environmental Law. But also the contempt with which it holds those who seek a greener future. The misogynistic and sexist treatment of a professional environmentalist working for a well respected international NGO by Geilser has rightly been treated as a scandal by the Austrian press.

Big thanks to the Pistyll Production boys and Bren Orton for representing us at the handover, current Corona Virus travel restrictions prevented us getting there from the UK.

2nd June 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

Why Dredging Won’t Solve Kendal’s Flooding Problem

Dredging is the act of removing loose sediment and other deposition from the riverbed and transporting it to another location.

During large-scale events the river is unable to cope with the volume of water that needs to be transported, and bursts its banks. We have noticed multiple people calling for the Kent to be dredged as a solution for Kendal. Below we detail some of the arguments against dredging, and why this won’t provide a solution for Kendal.

- Dredging has been shown to have little or no impact on the ability of a river system to respond to high water events. The increase in volume of a watercourse gained by dredging is minimal when compared to the volume of water requiring transportation. (Source)

- Dredging can increase the speed at which water moves through a physical location. This has many unintended consequences, the most notable of which is the increased downstream risk due to the flood peak travelling downriver faster (1, 2,3).

- Damage to wildlife and ecosystems.

Dredging severely impacts the habitats of invertebrates, which has a knock on effect further up the food chain on fish, and then on top predators such as Otters and Kingfishers. (Source)

Due to increased erosion from the faster flowing water it can have a big impact on the bankside species too. Existing species are removed and invasive species such as Japanese Knotweed colonise the banks of watercourses. (Source)

Increased erosion of the banks and bridges at dredging sites. Batman Bridge has already become unstable as a result of high water events. As dredging would increase the speed of water through town, this would risk the rest of our bridges, as well as increasing erosion of the banks of the river, requiring future engineering works and impact on our town (4).

Other protected species such as freshwater pearl mussels (5) and white clawed crayfish (6)are impacted by the removal of sediment and loss of habitat, as well as small riverside mammals such as water voles (7).

- Dredging cannot be carried out once and then ignored. It requires constant intervention and needs to be repeated frequently. Deposition occurs as a natural process, and continues to happen. In the Somerset Levels in 2014 dredging removed 220,000 tonnes of sediment, at a cost of £6million. This was less than the annual sediment load of the river, and so would need to be repeated annually in order to have any impact. After 12 years we would have spent the £72 million earmarked for the Kendal Flood Relief Scheme, and still not have a long-term solution (Source).

A river is a system of transporting water from the hills to the sea. In order to effectively manage flood peaks then slowing water transportation from our hills, rather than increasing the speed it can travel through our town should be the first point of call for any flood relief scheme. There are alternatives on the table that work with our local communities and protect our town. Lets not forget that the proposals from the Environment Agency will not protect Kendal from a Storm Desmond level flood, and yet will ruin our towns asthetics, whilst causing untold further economic damage due to the construction post COVID-19. Join us in writing to Giles Archibald to call on him to pause this scheme and allow us at the least to recover economically, whilst working on upland schemes to slow the flow. Call To Action

References

1 Newson, M.D.and Robinson, M. (1983) ‘Effects of agricultural drainage on upland streamflow: case studies in mid-Wales’, The Journal of Environmental Management, 17:333-48.

2 Robinson, M. and Rycroft, D.W., (1999) ‘The impact of drainage on streamflow’, in: R.W. Skaggs and J. van Schilfgaarde (Editors), Agricultural Drainage.

3 Sear, D., Wilcock, D., Robinson, M. and Fisher, K. (2000) ‘River channel modification in the UK’. in M. Acreman (Editor), The Hydrology of the UK, A Study of Change, pp.55-81.

4. Mathias Kondolf G. (1994) ‘Geomorphic and environmental effects of instream gravel mining’, Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 28, Issues 2–3, April 1994, pp. 225–243.

5. P.J. Cosgrovea and L.C. Hastieb (2001) ‘Conservation of threatened freshwater pearl mussel populations: river management, mussel translocation and conflict resolution’, Biological Conservation Volume 99, Issue 2, June 2001, pp183–190.

6. Stephanie Peay. Guidance on works affecting white-clawed crayfish (2000), Contract Reference: English Nature FIN/CON/139

7. Telfer S (2000) The influence of dredging on water vole populations in small ditches (Scottish Natural Heritage commissioned report F99LF13).

14th May 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

From Lockdown to Building Site

[vc_row type="in_container" full_screen_row_position="middle" column_margin="default" column_direction="default" column_direction_tablet="default" column_direction_phone="default" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" row_border_radius="none" row_border_radius_applies="bg" overlay_strength="0.3" gradient_direction="left_to_right" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_tablet="inherit" column_padding_phone="inherit" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" gradient_direction="left_to_right" overlay_strength="0.3" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]The Environment Agency have announced on Twitter that they still intend to start destroying Kendal’s river environment as soon as they can – straight from lockdown to concrete canal this Autumn.

The EA’s Stewart Mounsey posted on Twitter that work will start on the River Kent flood relief scheme in just a few months. Now is the time for local businesses and visitors to the area to object. Simply email Giles Archibald – the leader of South Lakeland District Council - at

g.archibald@southlakeland.gov.uk

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=".vc_custom_1590313051020{padding-bottom: 36px !important;}"]

Template for Kendal Businesses

Template for Kendal Visitors

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Why’s it so urgent now?

- Ecological vandalism: The river’s banks will be walled up and robbed of their trees and wildlife habitats. The ripping out of all Kendal’s beautiful riverside trees is a horrible thought, especially now that we are all realising just how lovely the walks along the banks of the Kent can be. There’s a profusion of flowers and tree blossom, the bats in the evenings, otters and kingfishers during the day, alternating between the dappled shade of the riverside trees and the sunshine of the green spaces at Sandy Bottoms, a haven for the herons, butterflies and wild flowers.

- Loss of business: While fighting for survival in the face of Coronavirus, Kendal’s small businesses will also need to brace for the effect of the EA’s phase one.

- Road disruption: The removal of the trees will cause a huge amount of disruption to Kendal’s road system, as huge trucks will need to be brought into the centre of town to remove the trees and transport them to whoever has bought the timber presumably.

- Health and safety: There will be many health and safety concerns with the felling of trees along a main road which will close at least one lane, if not the entire road.

- Parking: The transport for the contractors will need to be parked somewhere in town too. New Road? Canal Head? County Hall? Dowkers Lane? Wherever they put their vehicles will cause a huge amount of disruption to the people of Kendal, let alone any much-needed visitors to the town.

[/vc_column_text][image_with_animation image_url="2436" animation="Fade In" hover_animation="none" alignment="" border_radius="none" box_shadow="none" image_loading="default" max_width="100%" max_width_mobile="default"][vc_column_text]With tourism so essential to the town, who is going to want to attempt to get into Kendal with all the demolition and construction chaos? In the planning phase, the EA’s answer was to put signs on the M6 and on Kendal by-pass telling people to avoid Kendal due to the expected long delays. South Lakeland District Council is completely silent on this disaster waiting to happen for Kendal’s businesses.

Small businesses in Kendal should be very afraid – and visitors should be just as concerned. It’s time to hold our representatives to account. Write to your councillor now to help Kendal before it’s too late. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]With tourism so essential to the town, who is going to want to attempt to get into Kendal with all the demolition and construction chaos? In the planning phase, the EA’s answer was to put signs on the M6 and on Kendal by-pass telling people to avoid Kendal due to the expected long delays. South Lakeland District Council is completely silent on this disaster waiting to happen for Kendal’s businesses.

Small businesses in Kendal should be very afraid – and visitors should be just as concerned. It’s time to hold our representatives to account. Write to your councillor now to help Kendal before it’s too late. [/vc_column_text][image_with_animation image_url="2435" animation="Fade In" hover_animation="none" alignment="" border_radius="none" box_shadow="none" image_loading="default" max_width="100%" max_width_mobile="default"][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1st May 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

A response from the Tyrolean Government

Many thanks to all of you who wrote an email in objection to the construction of the TUMPEN-HABICHEN HYDROPOWER PLANT. One of the recipients has since responded, but the response addresses none of our concerns. We need you to take further action now!

AUSTRIAN RESIDENT? CLICK HERE TO TAKE ACTION

INTERNATIONAL SUPPORTER, CLICK HERE TO SIGN THE PETITION

Dear Madam or Sir!

Thank you very much for your Email to the members of the Tyrolean government concerning the Tumpen-Habichen power plant. On behalf of Vice State Governor Josef Geisler, as the responsible member of the government, I am pleased to answer you briefly.

With regard to the nature conservation proceedings, it should be noted that an appeal is currently pending before the Regional Administrative Court regarding the Tumpen-Habichen power plant. The Regional Administrative Court has to decide on the admissibility of the WWF’s appeal against the 2015 decision. In the opinion of the Office of the Tyrolean Government, an appeal does not have a suspensive effect. In this respect, and without prejudice to the legal opinion of the Regional Administrative Court, construction is currently legally possible. In this case, the building contractor acts at his own economic risk.

With regard to the water legislation procedure, it is to be noted that the authorities have determined there is no deterioration of the biological quality component due to the shift in the hydromorphological quality component of the river. These findings were confirmed by the State Administrative Court.

Against this ruling, an extraordinary appeal to the Constitutional Court and an appeal to the Administrative Court were filed. The Constitutional Court has already refused to deal with the complaint.

It is true that in the years following the financial and economic crisis in 2008 Tyrol generated more electricity than needed and thus exported energy – but this surplus has fallen to below 5% of electricity generation in recent years.

It is also true, however, that we in Tyrol are currently importing about 60% of our energy requirements in the form of energy generated with fossil fuels – i.e. Tyrol is not an energy exporting state, but an energy importing state that is fully dependent on fossil fuels. In order to eliminate this dependency and to contribute to climate protection, the Tyrolean State Government has set itself the goal of massively reducing energy requirements by 2050 and replacing imported energy from fossil fuels with domestic renewable energy. In all the energy scenarios examined for this purpose, electricity (for mobility, industry, heat pumps for houses etc.) plays the central role in meeting our energy needs and is a key factor in the success of the energy system transformation. This means that although overall energy demand is expected to fall, electricity demand will have to rise for energy system transformation.

The two essential resources for electricity generation that we have in Tyrol are photovoltaics and hydropower. The experts‘ scenarios show that, in addition to a massive expansion of photovoltaics on all favourably situated roofs, we also need a further expansion of domestic hydropower. For this reason, the Tyrolean state government has already decided in 2011 that by 2036 approx. 40% of Tyrol’s still usable hydropower potential, i.e. approx. 2,800 GWh, should be exploited.

The Tumpen-Habichen power plant is one of the projects that will help to achieve this goal. The planned generation of 61 GWh annually renewable energy by the Tumpen-Habichen power plant (which corresponds to the electricity requirements of approx. 15,000 households) does not solve the energy problem on its own, but – if approved in the course of the legal procedures – it will make a significant contribution to it.

With kind regards

Fankhauser

To address the main points of concern:

With regard to the water legislation procedure, it is to be noted that the authorities have determined there is no deterioration of the biological quality component due to the shift in the hydromorphological quality component of the river. These findings were confirmed by the State Administrative Court.

Above is a reference to the compliance of the project with the European Water Framework Directive (WFD). To be clear WFD assesses several components of a river system and the biological component is only one. Since the “Weser Trial Case C‑461/13 Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland v “Bundesrepublik Deutschland” it has been understood that even if only one quality element of a waterbody falls in status then the WFD is deemed to be broken.

The concept of ‘deterioration of the status’ of a body of surface water in Article 4(1)(a)(i) of Directive 2000/60 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy must be interpreted as meaning that there is deterioration as soon as the status of at least one of the quality elements, within the meaning of Annex V to the directive, falls by one class, even if that fall does not result in a fall in classification of the body of surface water as a whole.

Therefore, the permitting of the TUMPEN-HABICHEN HYDROPOWER PLANT would equal a breach of WFD and a breaking of European Law unless there is an overriding public benefit. This benefit is justified by the Tyrolean Government in the continued exploitation of new sources of hydropower.

The experts‘ scenarios show that, in addition to a massive expansion of photovoltaics on all favorably situated roofs, we also need further expansion of domestic hydropower. For this reason, the Tyrolean state government has already decided in 2011 that by 2036 approx. 40% of Tyrol’s still usable hydropower potential, i.e. approx. 2,800 GWh, should be exploited.

This policy is ecologically unsound and based on a now 10-year-old study; Energy self-sufficiency for Austria 2050

A far more recent study in 2018 by the WWF concluded that:

"The planned expansion of hydroelectric power in Tyrol is neither possible in an environmentally compatible manner nor necessary from an energy management point of view. An ecologically and socially acceptable expansion of hydropower (2014 to 2030) is to be planned with a maximum of 3,700 TJ (1,028 GWh). This goal can be achieved mainly through the hydropower plants already under construction, the modernisation and rehabilitation of already existing older hydropower plants (numerous small power plants) and the ecologically acceptable expansion of existing plants (e.g. Kirchbichl and Imst power plants)".

The results of this study show no hydropower plants are required on the Ötztaler Ache, the largest free-flowing river remaining in Tyrol. And that the further expansion of Hydropower in Tyrol when it already represents 96% of all electricity production (against 1.2% solar) is both ecologically unsound and lacks resilience to climate change impacts of glacier/snowpack sizes and river flows.

Save Our Rivers,WET - Wildwasser erhalten Tirol and WWF – Austria believe the response to be inadequate and that the construction of the TUMPEN-HABICHEN HYDROPOWER PLANT should be halted immediately and the plans for further hydro construction within the Oetz Valley abandoned

Please stay tuned for the next action in this campaign.

9th April 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

The Tumpen Dam and Water Framework Directive

We need you to take action now!

The Tumpen hydroelectric power plant is the first of many hydro developments planned for the Ötz valley by the developer TIWAG and it’s associates.

You can watch the video to understand the main concerns around its construction or check out our previous blog post here:

The construction of the Tumpen powerplant has been started under the cover of the Coronavirus lockdown of Tirolean citizens, despite several outstanding legal challenges.

One major concern is the breaking of the European Water Framework Direction through the damming of this currently free-flowing river.

Water Framework Directive (WFD) is the cornerstone of the environmental protection of Europe's rivers and freshwater ecosystems. It requires nation states to classify their waterbodies and make plans for the future development and protection on a river basin scale. The key tenant of the WFD is that no waterbody or section of a waterbody can be allowed to deteriorate from one classification to a lower classification unless there is an overriding public benefit and a number of strict criteria are met.

Article 4 Environmental objectives Section 7

Member States will not be in breach of this Directive when:

- failure to achieve good groundwater status, good ecological status or, where relevant, good ecological potential or to prevent deterioration in the status of a body of surface water or groundwater is the result of new modifications to the physical characteristics of a surface water body or alterations to the level of bodies of groundwater, or

- failure to prevent deterioration from high status to good status of a body of surface water is the result of new sustainable human development activities

and all the following conditions are met:

(a) all practicable steps are taken to mitigate the adverse impact on the status of the body of water;

(b) the reasons for those modifications or alterations are specifically set out and explained in the river basin management plan required under Article 13 and the objectives are reviewed every six years;

(c) the reasons for those modifications or alterations are of overriding public interest and/or the benefits to the environment and to society of achieving the objectives set out in paragraph 1 are outweighed by the benefits of the new modifications or alterations to human health, to the maintenance of human safety or to sustainable development, and

(d) the beneficial objectives served by those modifications or alterations of the water body cannot for reasons of technical feasibility or disproportionate cost be achieved by other means, which are a significantly better environmental option.

The Tumpen powerplant will cause the Achstürze section of the Ötz to fall from very good to good (1) . We therefore believe the permitting of the development to be in breach of European Law by not meeting requirements (d) and (c) of Article 4 section 7 of the Water Framework Directive.

The reasons for protecting the Ötztaler Ache in a free-flowing and ecologically intact condition for both environmental and recreational reasons are numerous and can be found on our previous blogpost here:

The benefits to “human health, to the maintenance of human safety or to sustainable development” can only be considered as the generation of electricity. However, Tyrol already produces more energy than it consumes, the vast majority of this (around 96%) was through hydropower .

In fact, a recent study shows that the whole of Austria can transition to 100% renewable energy without the need for new hydropower development in currently free-flowing rivers.

This over-reliance on hydropower alone leaves a far higher environmental impact than required for electricity generation and with lower snow fall and glacial retreat a lack of resilience in the face of global warming. With such small consideration made for alternative technologies such as solar it is impossible to see how requirement (d) above has been met.

Act now

We need you to email the responsible politicians with your concerns, around the exploitation of the Ötztaler Ache and it’s illegality under European Law.

If you live in Austria or speak German follow this link: WET email action

Otherwise download our template letter in English below:

DOWNLOAD TEMPLATE LETTER

make sure you add your own concerns , and your name then email to:

buero.landeshauptmann@tirol.gv.at, buero.lh-stv.geisler@tirol.gv.at, buero.lh-stv.felipe@tirol.gv.at, mail@freerivers.org

References

- ARGE Limnologie: Ergänzende gewässerökologische Stellungnahme betreffen EuGH-Urteil C-461/13 vom 1.7.2015 ("Weserurteil")

29th March 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

Unsere Ötztaler Ache / Our Ötztaler Ache

Stoppt den Staudamm in Tumpen / Stop the Tumpen Dam

The Ötztaler Ache the largest currently free-flowing river in Tyrol. Home to diverse riverine ecology, bank side alpine meadows and a mecca for white water kayakers from around the world. This jewel of Austrian rivers, previously home to the Sickline Extreme Kayaking World Championships is now threatened by multiple hydro power developments.

Petition Link, ACT NOW

There are estimated to be over 1 million dams fragmenting European rivers (Garcia de Leaniz, 2008) and the impact of this on biodiversity has been catastrophic. Populations sizes of freshwater species have declined by 81% in the period between 1970-2012 (Living Planet Report, WWF, 2016). This puts river and wetland as the most at threat ecosystems on the planet. The lose of such a large remaining natural river would be an environmental catastrophe.

More info here: Dam Removal Europe

What is Planned?

The Austrian utilities company TIWAG plans to dam and divert the water from 7 of the major tributaries of the Oetz and divert their flow through tunnels and out of the valley. 3 to feed the HEP plant in the Kühtai valley and 4 to the HEP at Kaunertal. In total 43% of the Ötztaler Ache’s catchment will be diverted out of valley. TIWAG also own a large share in the company building the Tumpen run of river hydroscheme currently under construction on the main Ötztaler Ache.

You can read more on these plans here: WILDWASSER ERHALTEN TIROL

The impact on the environment and recreational opportunities available on the Ötztaler Ache are stark. Studies by WWF show that these constructions are neither desirable nor necessary in order for Tyrol to meet its renewable targets:

The impact on the environment and recreational opportunities available on the Ötztaler Ache are stark. Studies by WWF show that these constructions are neither desirable nor necessary in order for Tyrol to meet its renewable targets:

“The Tyrolean goals for energy savings by 2050 are good and ambitious. However, the currently planned share of hydropower is excessively excessive and cannot be realized if Tyrol wants to take nature conservation seriously in the future. Our scenario and the goals of the state of Tyrol for the energy transition show that this is not even necessary. These hydropower plans are obviously relics from earlier times with different priorities. We reject climate protection arguments for excessive hydroelectric power today as a swindle on the label, ” WWF Austria

The Tumpen Hydro Scheme

Of immediate concern is the currently illegal construction of the Tumpen Hydro Scheme. Current plans would see the Achstürze Falls de-watered devastating this steep and ecologically unique section of waterfalls.

Also seriously affected would be the section of river immediately downstream. The world-renowned ‘Wellerbrücke’ rapids. Famous as the stage of the Sickline Extreme Kayaking World Championships. The upper section would run dry, and the lower section would no longer follow a natural flow regime – instead the levels would rise and fall according to how much energy the electricity company chooses to sell. The residents living near the planned reservoir in Tumpen are rightly concerned of the increased flood risk for Tumpen and Habichen and the siting of the planned reservoir within a mudflow area.

The impacts on ecology, landscape, recreational value and flood safety are huge. Far outweighing the benefits of the minimal amount of electricity the power plant would be able to produce – a mere 14.48 MW at maximum output.

The impacts on ecology, landscape, recreational value and flood safety are huge. Far outweighing the benefits of the minimal amount of electricity the power plant would be able to produce – a mere 14.48 MW at maximum output.

Plans for the scheme can be seen here: Tumpen-Habichen Power Plant Oetztaler Ache

In mid-March 2020, construction work started suddenly. With legal proceedings unresolved and Corona virus measures keeping people under curfew, the diggers moved in.

WWF Austria has filed an appeal against the plant’s nature conservation permit with the Provincial Administrative Court and an appeal against the "wasserrechtliche Bewilligung" lodged with the Supreme Court (VwGH) is still pending. The local citizens' initiative "BI gegen Wasserkraftanlage Tumpen" also has an outstanding appeal with the VwGH regarding the permit.

Local citizens are outraged in the way construction was started. There’s been no public information, no construction negotiation, and they feel the developers’ raid-like speed has taken advantage of the Corona crisis curfews to keep those who would wish to protest at home. Legally, though, construction sites can carry on working – which leaves this project a done deal if we don’t act now.

Local citizens are outraged in the way construction was started. There’s been no public information, no construction negotiation, and they feel the developers’ raid-like speed has taken advantage of the Corona crisis curfews to keep those who would wish to protest at home. Legally, though, construction sites can carry on working – which leaves this project a done deal if we don’t act now.

A petition has been started by WET - Wildwasser Erhalten Tirol and supported by the Free Rivers Fund, WWF Austria WWF Austria, the citizens' initiative "BI gegen Wasserkraftanlage Tumpen" and by us here at Save Our Rivers.

Please sign this here:

Petition Link, ACT NOW

12th January 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

Time is running out! Please help us to save Kendal!

As surveyors and contractors move in to start work, we’re still doing everything we can to save Kendal - but we can’t do it without you! We need your help right now!

11th January 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

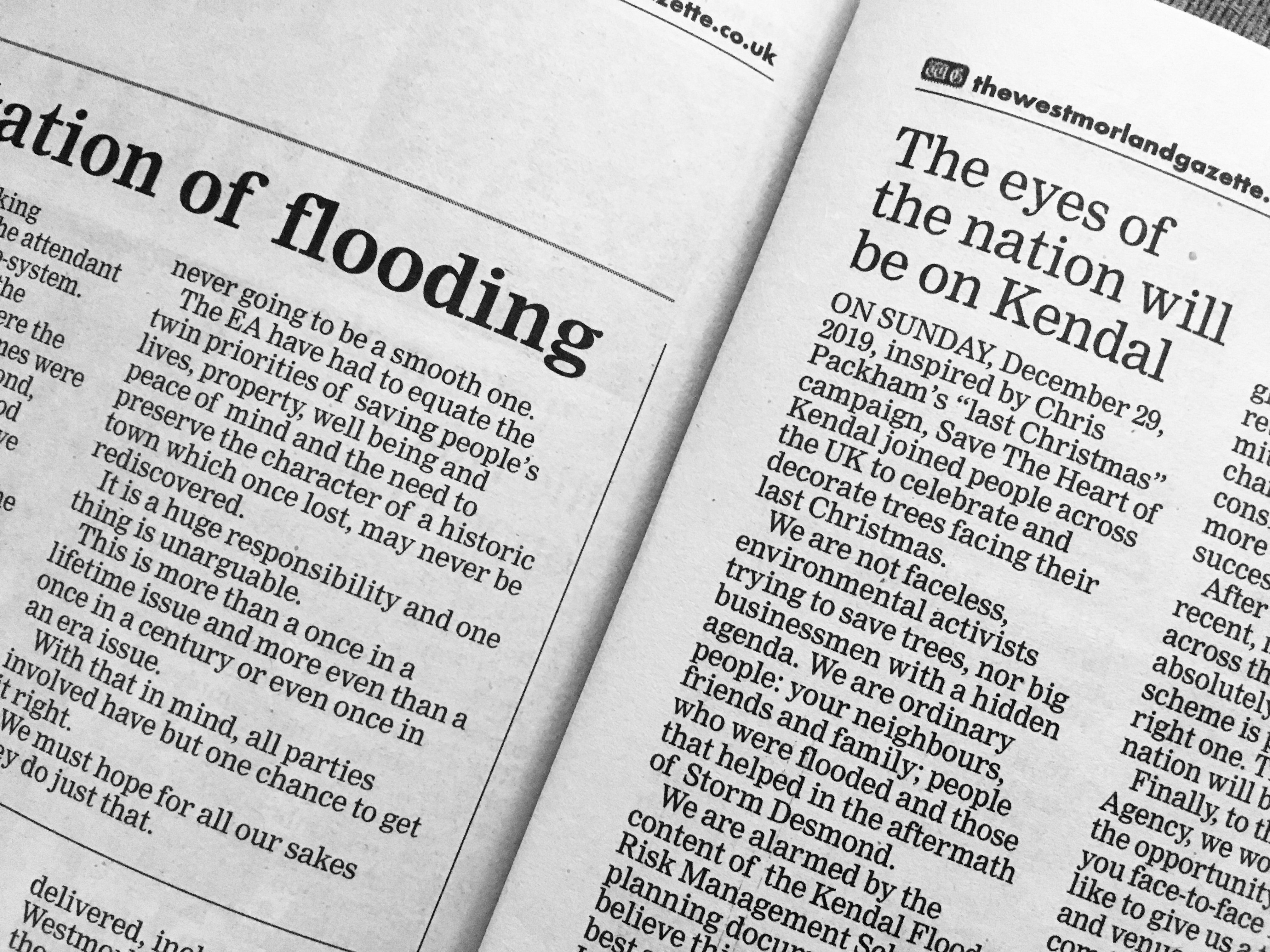

The eyes of the nation will be on Kendal

An open letter to Kendal in response to letters and spurious comments from supporters of the Kendal Flood Risk Management Scheme. Westmorland Gazette Letters, page 37, Thursday 9th January 2020.

9th January 2020 — Comments are off for this post.

Press Release January 2020

Comments from our new year press release were featured in a two page article in the Westmorland Gazette on Thursday 9th January 2020. Here is the press release in full.